The Suit:

Age of the

Androgynous Woman

Fashion has always been the hallmark of identity and self-expression, and woman has always been its phoenix: a creature of self-creation and self- destruction whose immortality signifies the timelessness of a beauty that continuously wills itself to freedom.

At seven years old, I had decided that I was going to ruin my Sunday dress – the last one of the two that I had – on the playground by climbing every tree and every wall, furiously hanging myself from the metal fences with their spokes and letting them tear the poofy, itchy part of the dress to shreds. After that cathartic exorcism, dresses and skirts were only bought on an event-related basis and it was not until I had started university that I began enjoying them. By the way, I have never had the privilege of wearing a hobble skirt: a hilariously despicable garment specifically designed to restrict the wearer’s strides and invented when women were becoming more activei; but being part of a melodramatic zeitgeist against skirts and dresses is a Lucifierian black mass that most girls will attend at some point in their lives. The communion we’ll observe is against the scratchy and uncomfortable kind. Against the “sit with your legs closed” and “o ngwanyana” (“you’re a girl” in SePedi) kind. They are behaviourally and psychologically oppressive and you can’t play.

Being that young and being told “you’re a girl” becomes a verbal chastity belt for Cyndi Lauper’s girls who just wanna have fun and come home in the morning light, but the world will not let you because “wHaT aRe YoU wEaRiNg (o_O)?!” Hearing that I was a girl was tense and grotesque, though I could neither properly articulate exactly why it made me feel that way, nor understand the miserable effect it was having on me. I was not sure of what being a girl meant I could be – or, rather who it meant I could be, but I knew it was not anything that the Green Goddess stands for.

Because a freedom policed beyond the ambit of the section 36 limitations clauseii is neither reasonable, nor justifiable. The Johannesburg taxi men of 2008 beat and stripped a woman for wearing a miniskirt, parading her naked around the taxi rankiii. Six years later, Ugandan President, Yoweri Museveni, signed into effect the ‘Miniskirt Law’, while the then Minister of Ethics, Nsaro Buturo, could be heard sincerely remarking that the “vice of miniskirts” was a traffic hazard that must be put to a stopiv. Everyone now openly knows that, from the moment that they are born, girls are forced to submit to patriarchal creeds and convictions without question, whilst “boys will be boys” persists as an antique anthem celebrating the quality of a blithe-like freedom that is deceptively intrinsic to the nature of males. In short, boys are not forced into dresses and the beings who are shape-shift into a strange and erotic thing. Simidele Dosekun captures this phenomenon perfectly when she writes:

“The kinds of patriarchal logics that underpin the widespread policing of women’s fashion and beauty practices are well-recognised and critiqued in African and other feminist scholarship and activism. We know that it is women who are figured as symbols/embodiments of the moral standing of community, family and nation, yet simultaneously as morally weak and polluting; that women are constructed as the guardians of ‘tradition’; that women are considered property, subject to male authority and domination; that it is our putative sexual propriety that matters most.”v

It is an identity that is violently foisted upon the child-bearing faction of the human race. However, on the other end of the spectrum, an uncomfortable event occurs when a man decides to bind himself in a dress, turning himself into the effeminate image of gay pride, or a “moffie” (often a disrespectful word) as he is popularly referred to in certain coloured communities of South Africa. This event highlights an important perspective: that a woman is a lesser being and wanting to be like her, or exhibiting traits that are considered feminine, signals the depreciation of masculinity in an individual who must not be taken seriously; it is like the telling of a self-deprecating joke that completely misses the mark and lands in cringe-terrority. Men displaying “womanish” traits are not considered “King”, even by their female counterparts. Empathy, compassion and meekness do not fit into a pair of chinos.

Pharrell Williams featured in GQ cover, November 2019. Gown, by 1 Moncler Pierpaolo Piccioli

Source: www.gq.com

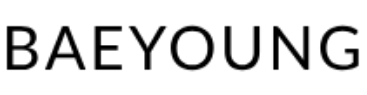

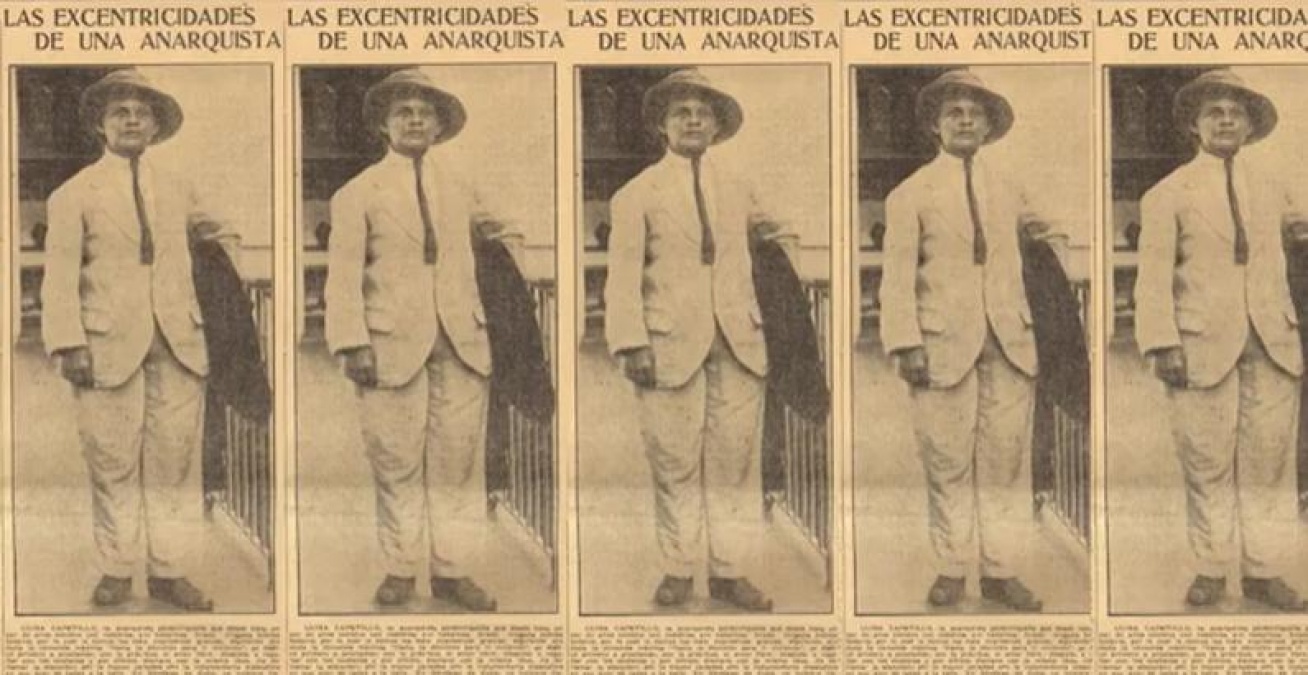

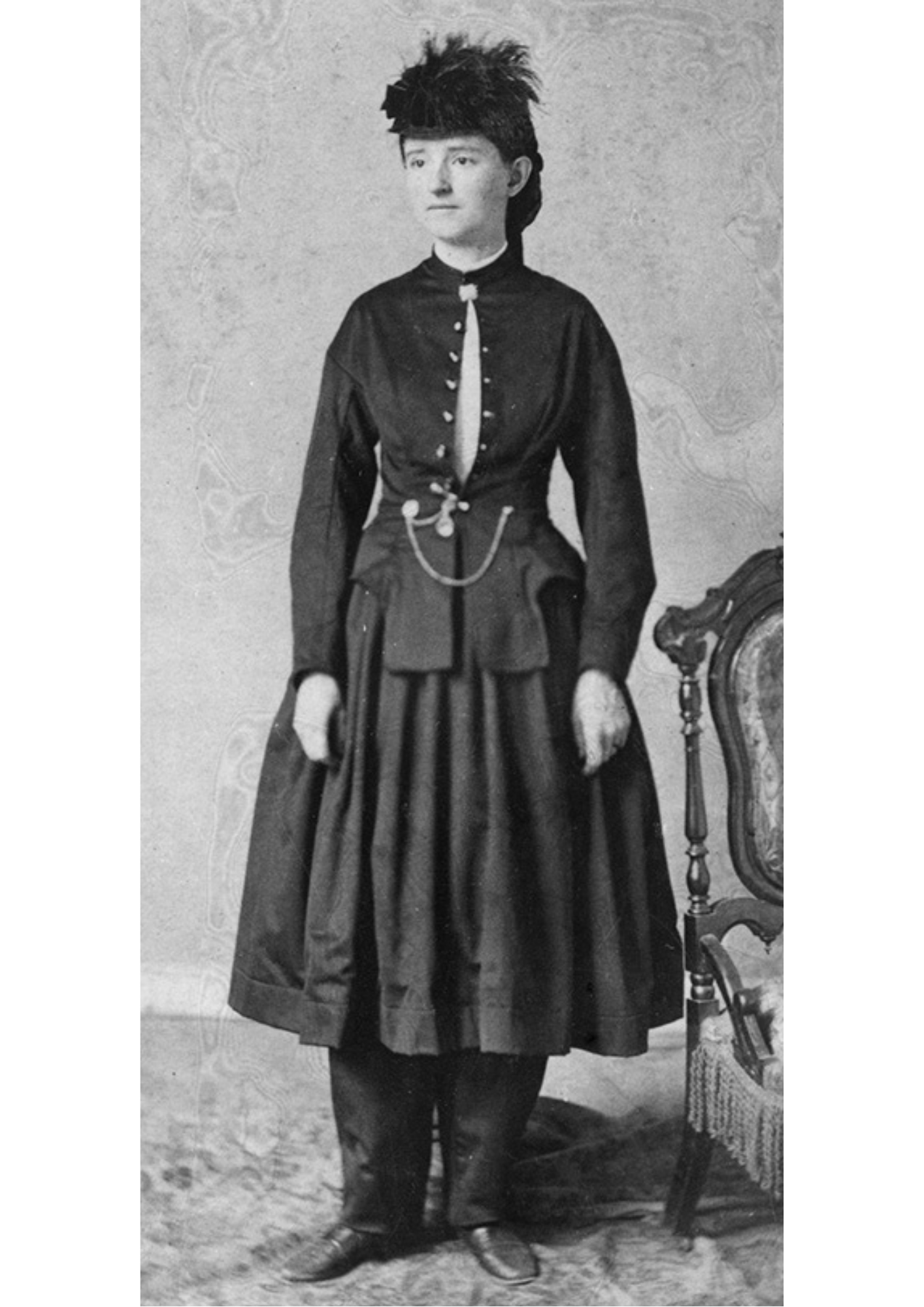

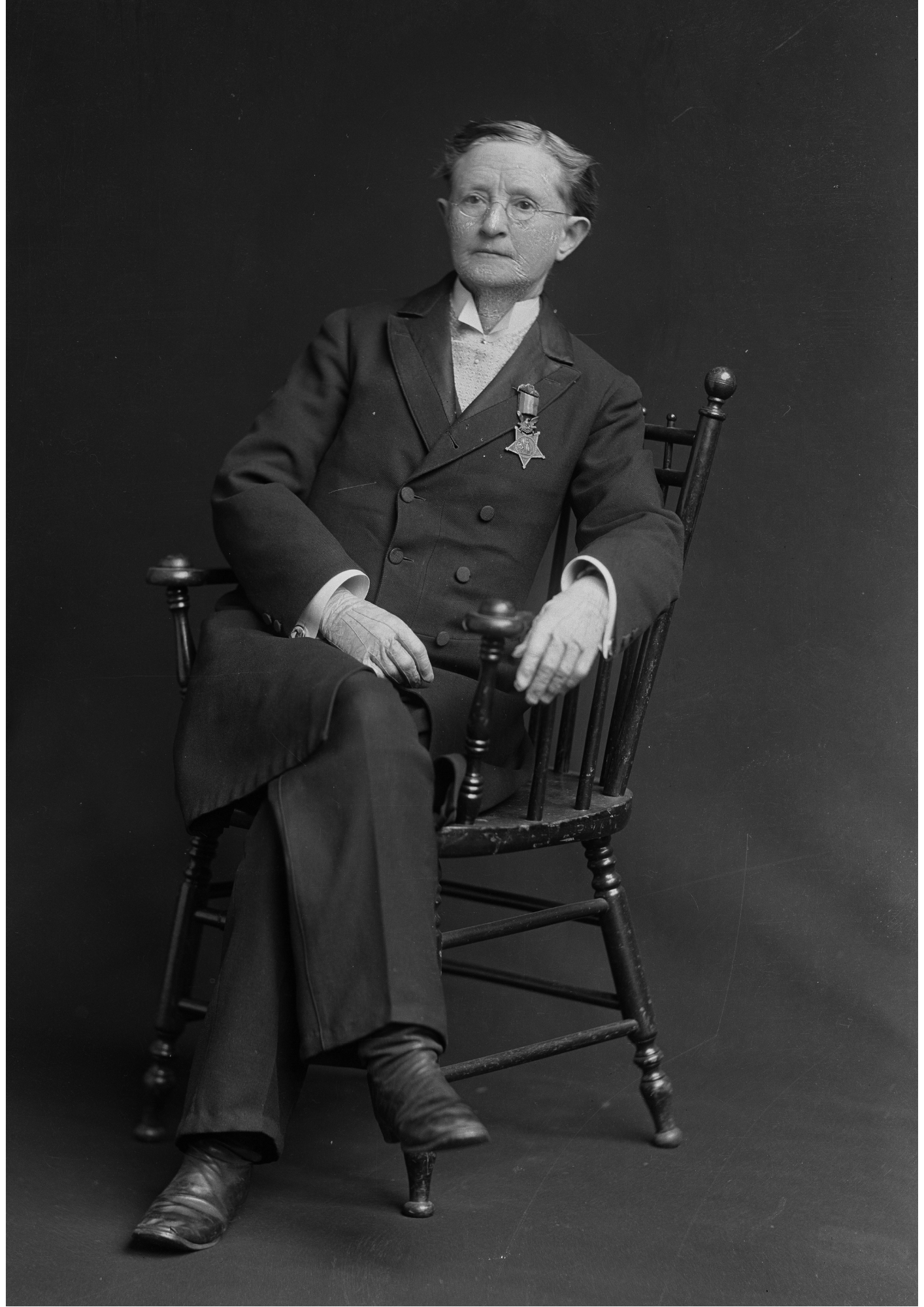

A woman acting and dressing like a man, however – regardless of her sexuality – is a dangerous and threatening subject. In 1912, a woman could be jailed for wearing trousers and Luisa Capetillo became the first woman in Puerto Rico to land this achievementvi. Before that, Elizabeth Smith Miller acquainted Amelia Bloomer with the freedom of the “Turkish dress” – now known as the Bloomer due to Bloomer’s fierce promotion and advocacy for the garmentvii; and then there is Mary Edwards Walker, well ahead of her time in 1913, who gets arrested a second time for wearing trousers at the modest age of 80, adding onto the growing list of significant triumphs in American fashion history. Everyone loves how women’s continued disobedience and rise to power was successfully tailored by Coco Chanelviii and the irreverent Les Smoking Suit of Yves Saint Laurentix. ‘The Menswear Phenomenon’ taking hold of the West enforced the image of a masculine woman who was mentally superior to the commodified observation of her body and who demanded to be recognised, because she is an equal.

Elizabeth Smith Miller, from a 1908 publication

Source: www.wikipedia.com

A portrait of Ms. Amelia Bloomer in her namesake dress which started an international trend.

Source: Getty Images

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker wearing trousers under short, layered skirt; unusual attire during her era.

Source: www.wikipedia.com

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker photographed by C. M. Bell

Source: www.wikipedia.com

Janelle Monaé in classic black and white suit at the Austin Music Hall during SXSW, March 2009

Source: www.wikipedia.com

In Africa, with her multi-layered influences of traditional, colonial, domestic, international, and neo-colonial fashion, women striding into trousers, though widely accepted as a norm, is still an on-going event. There exists an abnormal number of fossilised commandments. Schools, particularly those with a strong religious fixation, command that girls wear skirts.

Culture commands that women wear skirts at cultural events and gatherings. Fathers command that their daughters never walk under their roofs in trousers. It is in this context that common sense arguments for the practicality of trousers turn into political defiance when women, disregarding juridical and legal sanctions of their image, seek to destroy their objectified identity through wearing the pants and a matching blazer that emotes rigid, padded shoulders.

And what does it mean to wear a suit; to wear a subverted statement of our sexuality and gender? On August 7th, my sister’s head caught the buzzcut season’s flames. In minutes, she was completely bald and then, excited and inspired by her culturally taboo bare- headedness and the African les sapeuses of the fashion religion known as La Sape, we had the idea to celebrate our womanhood by taking pictures for women’s month – but in trousers and jackets. We raided our closets for our finest threads and went marauding – a complete success when we found the horses, too.

The freedom to execute masculinity on our female bodies was an interesting experience. Women’s fashion has the most varied tastes, operating under heavy codes of moral correction vis-a-vis the fetishised and mannequin-ised form of the wearer. In a dress or skirt with a longer hemline, a woman is wife material. In the miniskirts and skimpy clothing of what Ariel Levy aptly refers to as “raunch culture”x, she is the self-liberated WAP. In trousers, she marched into the workforce at the advents of both World Wars, conducting hobble skirt races for leisure and laughing with derision at the hazardous insistence that her legs stay tied together.

I believe that our shared experiences as women have allowed us to curate an identity that is both masculine and feminine: the andr and gyne, a theme that was progressively celebrated by Zanele Muholi’s observation of lesbian pageants through her photography. The series, titled Miss Lesbian, reconstructed the visibility of the rare stages where beauty is performed on masculine female bodiesxi. However, being androgynous and wearing clothes is not an innate characteristic of one’s sexual experience of themselves. The androgynous being is powerful and empathetic, compassionate and assertive, the strong and silent type of 1956 when they marched to the Union Buildings in protest against the proposed amendments to the Urban Areas Actxii, because being about ending the silence hanging over the suffering that women’s bodies and identities are subjected to is far too important. The trauma caused by the “gendering process” proves that it was never necessary to wrap ubiquitous habits of self-emmolation around the feminine psyche.

In 1956 20,000 Women March To The Union Buildings In South Africa To Protest The Pass Laws Under The Apartheid Government.

Source: www.pinterest.com

In the air-brushed society of fashion and HD, conversations about femininity continue to reach for the blurry ideal that conjures up the personality of the trouser alongside that of the dress – which is also beginning to show teasers of debuting its return in menswear fashion, nestling itself into the cracks of society’s collective cognitive dissonance. It’s nothing to be ashamed of, the realisation that we were wrong about ourselves and one another, but it is a wrong that must be burned at the pyre and transcended.

The present-day message is clear: modest or raunch, women are asserting the right to build their own identities that are independent of phallic narratives. Arguments for or against being “girly” or “boyish” are being deconstructed to reveal social constructs that exist due to centuries of conditioning. A well-rounded woman (and man) is left to be comfortable with who she is, not forced to repress aspects of her personality. Suits and dresses are both symbols of power, illustrating women’s depth, adaptability and multi- faceted characters and experiences. As Niariu of Les Amazons remarks, “Femininity [and masculinity] are in everyone, male or female.”xiii

After all, a girl on fire is not just a girl.

The Suit: Age of the Androgynous Woman

The Suit: Age of the Androgynous Woman

Photo credits: A HUGE thank you to Elrina and her daughter, Sade who made it possible to take pictures on their grounds and with their horses. The name of their stable is Havilah Horses. The horses appearing in the pictures are Madeira Bess (the lighter horse) and August (the darker horse).

i Blanco J, Hunt-Hurst, Kay P, et al. 2015. Clothing and fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe [vol. 4]. ISBN 9781610693103.

ii Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.

iii Sibanyoni, M. (2012/08/10). Mini Skirt Attack Victim Disappointed. Retrieved: https://ewn.co.za/2012/08/10/Santaco-apologises-victim-disappointed/amp (accessed 08/08/2020).

iv Anti Pornography Act, 1 of 2014.

v Dosekun, S. 2016. ‘Editorial: The politics of fashion and beauty in Africa.’ Feminist Africa 21: The politics of fashion and beauty in Africa. Vol 21. Issue 21. 1-6.

vi Spiegel, T. (2019/11/18). Luisa Capetillo:Puerto Rican Changemaker. Retrieved: https:// blogs.loc.gov./international-collections/2019/11/luisa-capetillo-puerto-rican- changemaker/ (accessed 06/08/2020).

vii Chrismas-Campbell, K. (2019/06/12).When American Suffragists Tried to ‘Wear the Pants’.Retrieved:https://amp.theatlantic.com/amp/article/591484/(accessed:06/08/2020

).

viii Vernose, V. (2020/01/05). The History of the Chanel Tweed Suit. Retrieved: https://www.crfashionbook.com/fashion/a26551426/history-of-chanel-tweed-suit/ (accessed: 07/08/2020).

ix Shardlow, E. (2011/08/08).How Yves Saint Laurent Revolutionized Women’s Fahion By Popularizing The “Le Smoking” Suit. Retrieved: https://www.businessinsider.com/ysls- greatest-fashion-hits-2011-8?amp (accessed: 06/08/2020).

x Levy, A. 2005. Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture. New York: Free Press.

xi Matebeni, Z. 2016. Contesting Beauty: Black Lesbians on the Stage. Feminist Africa 21: The politics of fashion and beauty in Africa. Vol 21. Issue 21. 23-36.

xii The 1956 Women’s March, Pretoria, 9 August. Retrieved: https://www.sahistory.org.za/ article/1956-womens-march-pretoria-9-august (accessed: 06/08/2020).

xiii Humphries, S. (2020/01/22). This African group’s music champions rights – and love.

Retrieved:

https://www.csmonitor.com/layout/set/amphtml/The-Culture/Music/2020/0122/This- African-group-s-music-champions-rights-and-love (accessed: 08/08/2020).

Lerato Ramodike is a Pretoria based writer, she’s a novelist, short story writer and visual artist.