TOP BOY:

THE MAKINGS OF A BLACK MAN

An Exposition Of The Black Mans Masculinity

In The 21st Century

The 21st century in a patriarchal society is:

where in South Africa, more than half of all the women murdered in 2009 were killed by an intimate male partner;

when Jaden-Son-of-Will-Smith wears a skirt and becomes the face of a women’s wear ad campaign;

when black men are beasts dangerous, leaving behind them legacies of fatherless households and raising the sons of other men in a way that turns these boys into complicit practitioners of whatever it takes to be a man;

when british series Top Boy, inspired by real events, is allegedly not as grim and as bleak as the situation of the ‘roads’ in the drug and sex-trafficking scene of London are (in order to make it more viewer-friendly), but the creators still succeed with protraying to the viewer the truth and direness of the situation.

And do we remember that time when LeBron James and Gisele Bundchen appeared on the cover of Vogue? Yes, the one that distinguished him as the first African American man to appear on the cover of Vogue. Yes, the one that was a collectively humiliating experience for black men, because of the discovery that the pose was inspired by a retro poster of King Kong. LeBron’s mouth was open in a twin-like fashion to that of the shouting ape, which is heard in the theatres sounding it’s barbaric ‘YAWP!’ across the rooftops of the world.

LeBron James and Gisele Bündchen in April 2008 US Vogue cover

The 21st century:

when women, living in this man’s world, bear the onus of protecting themselves from the Noise of men.

A Noise symbolically dealt with by Patrick Ness in his Chaos Walking trilogy series, where the men, and only the men of that world, have caught a disease called “Noise” whose only symptom is that the thoughts and feelings of men “spill out into the world in a shout that never stops”.

It is this aggressive imagery that illustrates the way in which the society of Top Boy establishes the quintessence of a man as an identity that is inherently destructive, violent and doomed to freedom from the law, a freedom that outlaws him from legal protection even when he is well-behaved. A black man’s droit becomes that which is relentlessly antithetical to the identity of the sexually objectified ‘body in terror’ that is assigned to the women (such as Jamie’s supplier-with-benefits who was kidnapped and harassed at gun point) – a terror, a horror, a ‘vulnerability’ that a roadman cannot express without it meaning that he is no longer a man.

And, while this is generally true for all men, it is especially true for the black man.

Jamie played by Michael Ward

In the first season of Top Boy, we are introduced to Dushane and Sully: 26-year old roadmen whose ‘food’ gets nicked. Their supplier is a well-dressed white man who, up until the second time their drugs get stolen, allows them the luxury of guns. However, while guns are popular on the drug scene, the practicality of a knife – the ultimate phallic symbol – is a tool that finds itself oft preferred by the younger roadmen of London drug culture, because they are more discreet, because you’re just a boy and your fists alone aren’t going to help you, innit?

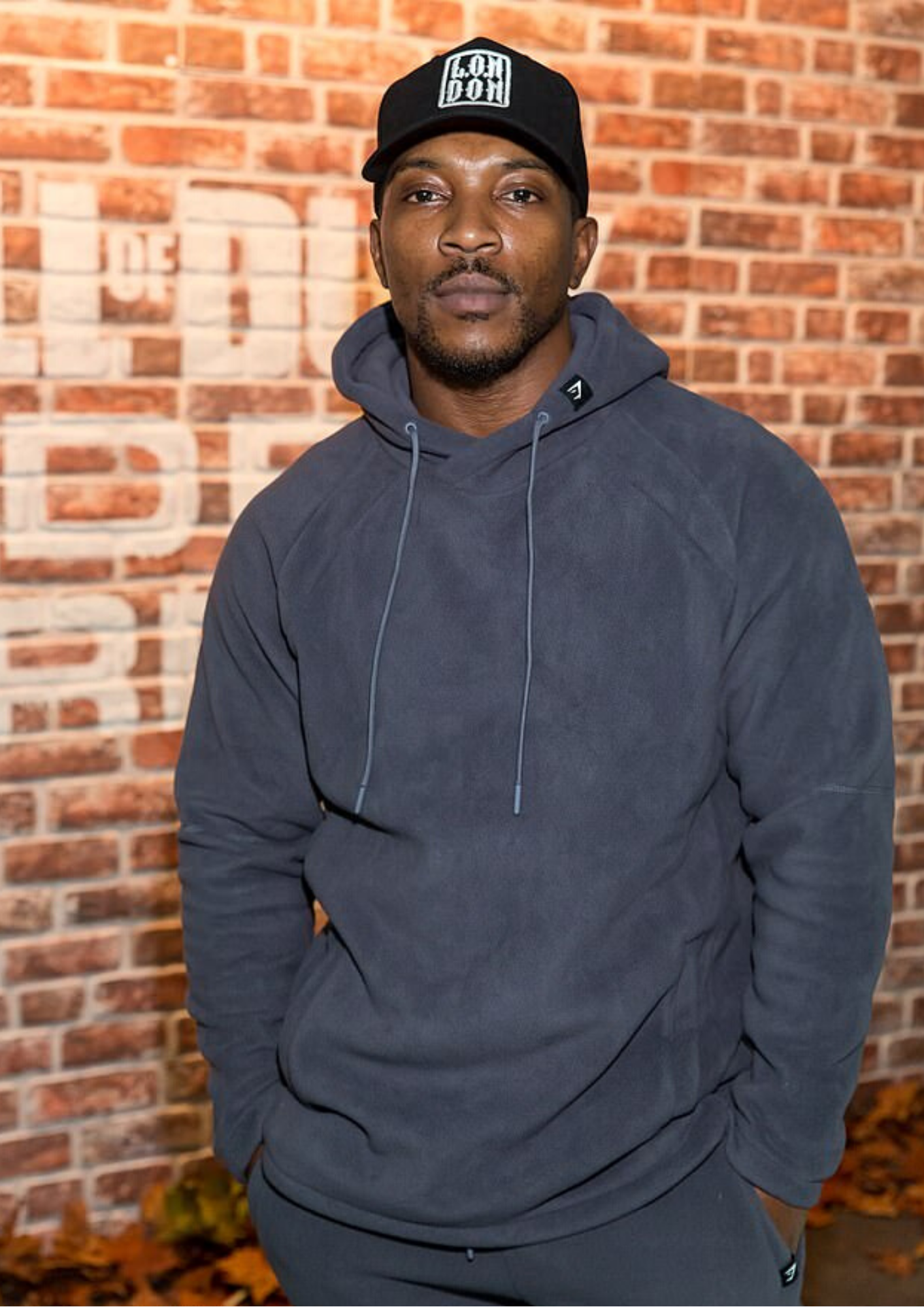

Ashley Walters who plays Dushane

Kano who plays Sully

The series largely follows the lives of these two men (and their gang, which initially has three women, and then just one) involved in the drug-dealing gangsterism ’appenin’ on the estates of London, detailing their sacrificial, and often messy, journey to being the ‘top boy’ of the roads. Moreover, because their suppliers are foreign white men, whose social standing is much more protected by virtue of the simple stroke of the kind of luck a lack of melanin affords you in this world, it is Dushane and Sully who are hunted and investigated by the police as being the sole source of the problem. In all fairness, all individuals involved ought to be investigated, however the image of Dushane being interrogated by a female investigator (and male, but the woman did most of the talking) is reminiscent of Coolio’s music video for Gangsta’s Paradise. Ironically, the fear for his life and the difficulty of surviving that Coolio emphatically expresses in his song is lost on Dushane, who we later hear bragging to his solicitor about building and owning the Summerhouse gang shortly after his run in with the feds. His solicitor (yes, a woman, now move on) tersely congratulates him on being the “king of a shit hole”.

Dushane being interrogated at the police station

And rightly so. The London estates are mostly known to be unsafe places coated in grit and grime, with redditors warning tourists to steer clear of them. But it is also the areas where typically marginalised and disadvantaged groups find themselves trying to make a living in the heat of all this crime and violence. Meet Ra’Nell. A 14-year old boy who’s mother suffers from debilitating depression. He does his best to avoid the clutches of Dushane and Sully, who attempt to recruit him by identifying him as their ‘brother’, offering him their protection should anyone give him trouble, and impressing upon him that he needs to step up to be a man so that he can take care of his mother when she gets back from the mental institution. He refuses their gestures – and their free money – having had the experience of a father who was a roadman and who he clearly still despises.

Ra’Nell and Gem

In a painful twist of fate, however, Ra’Nell ends up innocently helping his mother’s friend, a pregnant ‘milf’ by Gem’s – Ra’Nell’s best friend – standards, to grow a weed farm. And while she isn’t involved with the Summerhouse gang (yet), it is still a dangerous business, one that Ra’Nell loses a father-figure to and whose anguish is dismissed by Sully who “never meant for any of this to ’appen’” in case any of us think he did.

In season 2, we see a slightly older Ra’Nell and Gem drift further apart: Ra’Nell’s motivation for the choices he makes is not to be the man that his father was, while Gem’s motivation is money. Lisa, Ran’Nell’s mother, is completely cured of her depression, therefore Ra’Nell no longer feels the pressure to ‘man-up’ and can now focus on training for tryouts for his school’s soccer team. Unfortunately, being associated with Gem results in a failed attempt to stand up for his friend to a drug dealer – sans knife – which means that Ra’Nell gets a beating, one that neither he nor his mother can report to the police. And when his mother tells him that she will do her best to make it right, he brings home the reality that she is nothing but a woman who “don’t know nuffing about the roads”.

Ra’Nell arguing with his mother

It is often this physical powerlessness against older boys and men that finds the sons of black, single mothers pressured into the arms of these same men who promise – and deliver – lifestyles of money and all the things that their mothers (and child support) cannot provide for them. The boys are convinced, both by their mentors and by themselves, that they are doing all these things to fit the profile of being a provider for the women and children in their custody. After all, being a provider is a requirement that Ats, at the age of 12, must step in to fulfill so that him and his mum aren’t kicked out onto the streets, because his mother runs the risk of being deported should she be found working.

It is a requirement that a man needs to adhere to in order to secure within themselves the manly ‘sameness’ that they recognise in other males who have also been, and are still being, socially conditioned to acquire by virtue of the actions that they take in building their characters – like knives.

Knives that not only act as weapons against the world, but against their own internal struggles, against the things that hurt them. It is this facet of black diamonds that is oft unseen in the media: vulnerability, a human characteristic that black masculine roles do not usually expose. Think the wild, irrepressible fear and desperation of Solomon in Blood Diamond. And Season 3 of Top Boy, listed as Season 1 on Netflix, portrays this reality in a powerfully honest and realistic way, not turning the viewers face away from Sully’s burning tears when he looked at the picture of his daughter – so close to his release date, so close to seeing her again. And then there was when Dushane speaking to his father in the streets without so much as a handshake, the large, deliberate space between them a gaping reminder of all the things that his father put him through, of how Dushane had to be a father to himself, however corrupt, however desperate – in order to survive.

Dushane meeting his father in the street

And then there was Jamie. Confident. Strong. Intelligent. And driven. Jamie, who promised his parents that he would never leave his brothers, is forced to leave them for his own safety. And it’s not a “business as usual” moment. He’s heart-broken. He crumbles into a brittle pile of tears in the arms of his right-hand man – who comforts him, and there is nothing embarrassing or weak about the moment. He was only eighteen when his parents died and he was forced to become the legal guardian of his two brothers. He was only eighteen when he promised his dead parents that he would never leave Aaron and Stef, but then here he is, leaving them once more without a parent.

Jamie in the park with his younger brothers Aaron and Stefan

The maxim “If one of us falls, we all fall” found in Patrick Ness’ dystopian novel The Knife of Never Letting Go (the first book in his ‘Chaos Walking’ trilogy) is a nuanced highlight of the deep fear that men experience in regards to the loss of their masculine identity. However, like in Ness’ novel, the creators of Top Boy achieve a nuanced, dynamic and multi-dimensional portrayal of a black man, one who’s nerves are strained with self-awareness, like in the moment when Sully, whilst awkwardly watching his daughter from a distance, says, “I’m a man who stinks of jail. She deserves better than that.” It is only when his ex-girlfriend catches him walking away from them (at what must be the tenth time he’s been lurking) that he agrees – unsure of himself – to come and see his daughter.

“You’re not my father.”

And Sully blinked in pain, understanding that she probably no longer remembers him. It is a situation that is a traumatic result of the choices that he made. A realisation that a black man is not just “chaos walking”, because that chaos is a choice. Because that manliness, that fatherhood is something that you do, and you can only do it when you are there.

Sully meets his daughter after coming out of jail

It is in this way that Sully’s character matures, becoming increasingly disenchanted with the ‘trap lyf’ that Dushane is still obsessed with. After single-father Dris is found to be disloyal to the Summerhouse gang, Dushane and Sully must kill him in order to protect the integrity of the gang. And Sully, who lost all rights to build a relationship with his daughter, is the one who has to do it. Asking Dris, “Between you and me: Why?”; when the camera draws itself away from the scene as a gunshot rings out. Admittedly, I’m just as hopeful as fans (because I’m also fans) that Sully didn’t shoot Dris, because we didn’t see the body, because Sully wants to be a better man.

Sully on the roof top with Dris

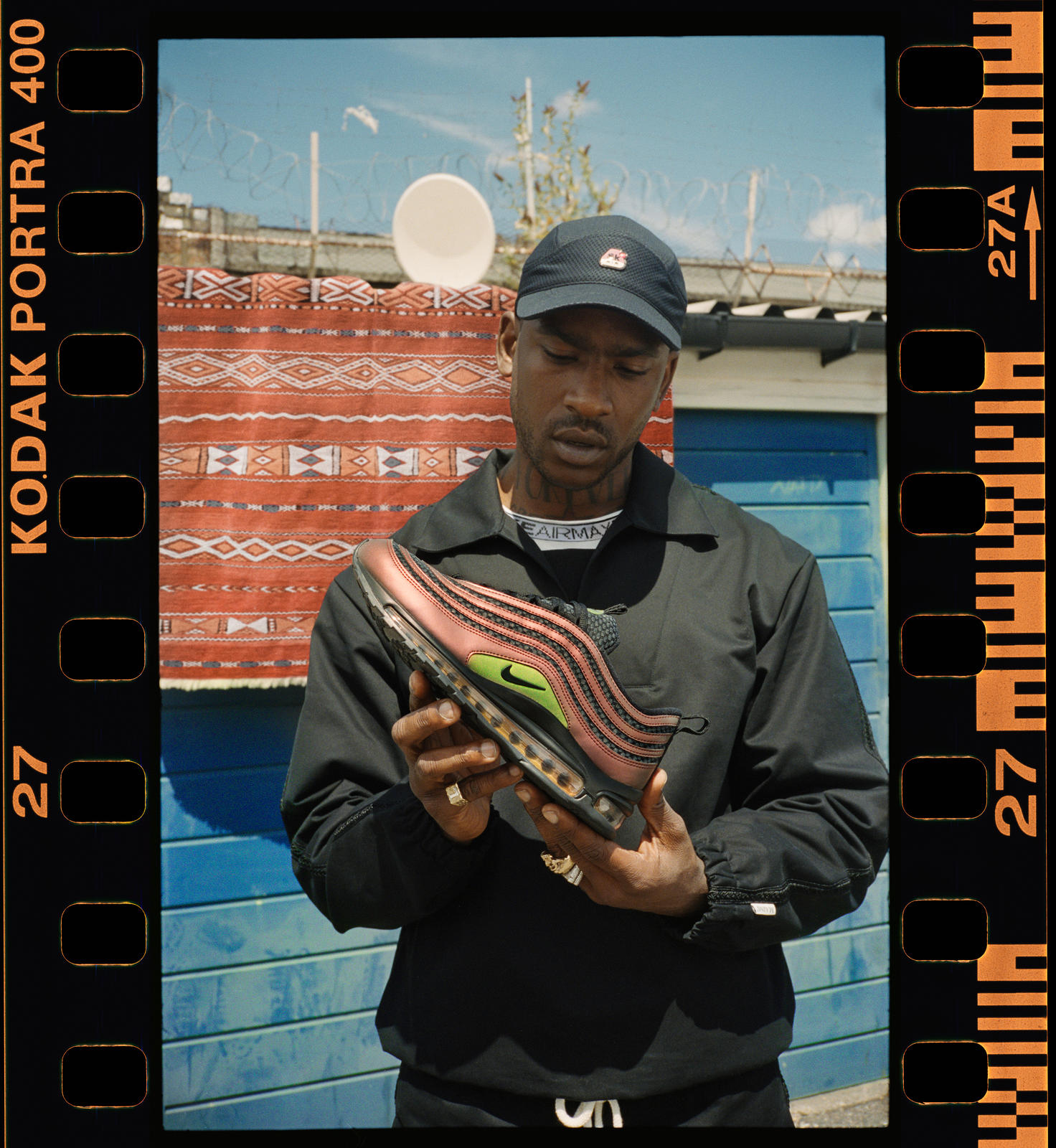

On a more fashionable note, Drake’s revival of the series is loaded with emphasis on grime culture through the use of music, language and men’s wear fashion that still skirts the skirts of Louis Vuitton. Coming a few years after grime artist Skepta’s collaboration with sportswear giant Nike that saw the production of three different kinds of Air Max, the drug dealers in the new season of the Summerhouse estates are well-dressed, donning impressive profiles that are clear acknowledgments of “grime”, whose western acceptance as a musical genre came with the discovery of the aesthetic of the roadman dogging the British streets.

Skepta with his Nike Air Max 97 Sk

Skepta’s Nike Air Max 97/BW SK

Skepta’s Nike Air Max Deluxe SK

However, it is more than mere matching tracksuits and the posturing of Jamie’s black and blue parka, more than the nondescript, black-uniformed silhouette of Dizzie Rascal’s Boy In Da Corner album cover that completes the roadman image with Nike Air Max BWs – the staple trainers that come in handy when making a quick-getaway (or in a chase, like when Dris is running after Gem). It is the practicality of a knife, of a hoodie as a coat of armor that acts as a defense mechanism against CCTV cameras and feds, as Kano says in Hoodies All Summer, “We’re resilient, we wear hoodies all summer. We’re prepared for whatever.”

Kano’s Hoodies All Summer album cover

Dizzie Rascal’s Boy In Da Corner album cover

Lerato Ramodike is a Pretoria based writer, she’s a novelist, short story writer and visual artist.