Made In China

Asian Aesthetic Through The Looking Glass

About a year ago, Nepali fashion designer, Prabal Gurung, brought the rural vogue of his home to the runways of the contemporary Big Apple. The set was ceremoniously adorned with the goodwill of prayer flags that were interlaced among dead trees whose sterile branches were clinging to dead leaves; a backdrop that was, in a manner both exquisite and humble, referentially symbolic.

The collection? Sportswear – as beautiful and as colourful as its inspiration and artisans.

Of course the hints of the arid landscape and the chandelier of prayer flags were a necessary context, without which the source of Gurung’s ingenuity would have remained a “far-flunged” mystery to New York’s elite attendees, as Vogue so aptly indicated. It was more than just sportswear: it was an artistic statement of cultural pride and significance.

Prabal Gurung New York Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2019

Source: OnoBello.com

The validation of Asian clothing on western fashion runways and editorials is not something new, however, with proof being the fashion industry’s meteoric rising interest in the artistry and portrayal of Asian aesthetics by Asian designers; and the current testament being that they now commonly frequent European and American runways and fashion editorials. Think the unbridled molten dragon dresses of Guo Pei and the Japanese-accented mannequins of Commes des Garçons (both of whom dressed Rihanna).

Model in a dragon dress from Guo Pei’s “Story of Dragon” collection.

It becomes clear that Asian fashion designers draw heavily from their roots, expressing their clothing through the creative cogito of weaving their art with the unavoidable denominator of region paired with the time-conscious triplicate of ancient, modern, and foreign devolution. It is in this sense that fashion reveals itself to be a powerful form of art, and being classified “haute couture” is another step forward in establishing the other-worldliness of heavily cultured pieces in a world seeped through with increasing individualism.

Rihanna wearing Commes Des Garcons at 2017 Met Gala

The ambit of Asian fashion encompasses culture, tradition, spirituality and status. Seen in this light, it becomes hard to miss the possibility of an existing double-entendre in Rihanna’s 2015 Met Gala dress. It took Guo Pei and her 500 artisans two years to make, with Pei citing the source of her creativity as the ‘extravaganza’ of Chinese royal history – a history she’d heard from her late grandmother (who lived at the end of the Qing dynasty) who described the fantastic court garments that could no longer be worn after the fall of the Empire.

One hundred and nine years later, and we are treated to the sight of literal, superstardom royalty gliding across the red carpet, with ‘servants’ rushing to re-arrange the dress – whenever Rihanna needs to walk over thataway – and providing the onlooking peasantry with the maximum effect of a wealth that exudes excessive opulence.

Rihanna at the “China: Through The Looking Glass” Met Gala in 2015 ( Getty Images )

“IT IS AS PAINFULLY CLEAR AS THE ACHING BEAUTY OF THAT DRESS THAT FEW AMONG US ARE TRANSCENDENT ENOUGH TO TRULY PULL OFF A DRESS SO INSPIRED BY SOVEREIGNTY. MEANING YOU COULD WEAR IT, BUT I DOUBT THAT IT WOULD HAVE THE SAME EFFECT.”

Knowing that the dress was motivated by the regalia of the ruling classes made the imperialist denotations of the event apparent. Even prior to the Qing dynasty, the classic robe or tunic, whose association with Asian tradition is near-subconscious, was an outfit that was used to highlight status.

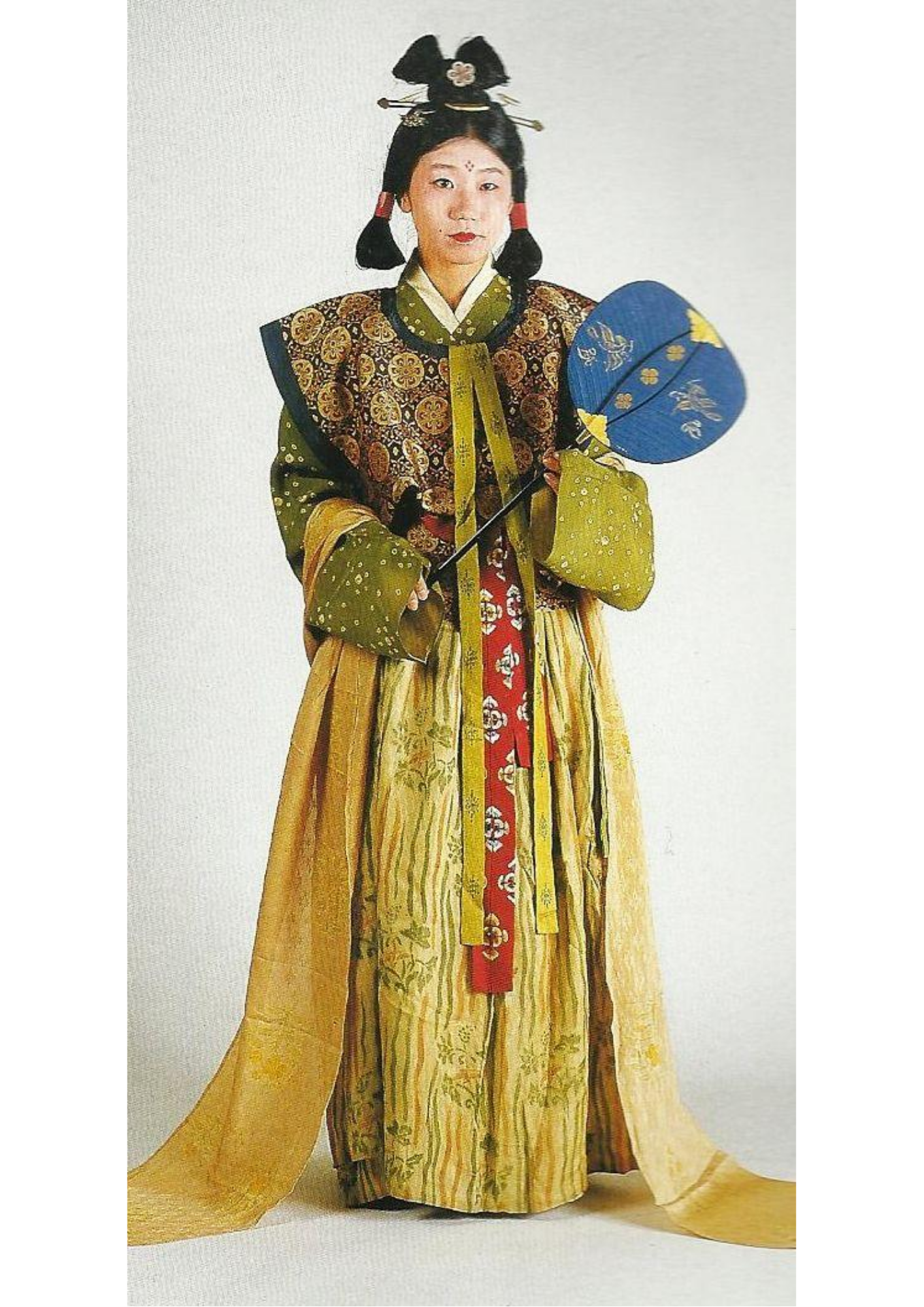

The tunic itself, whose ancient documentation by Diodorus Siculus describes the curious Celtic wardrobe basic as “astonishing”, had far-reaching impact; spreading its contours across Asia and tailoring itself via the assimilation of the cultural requirements of each country. It became the basic garment for both sexes, which could be worn either long or short with trousers or a skirt (for both men and women, and not in kilt format), or sans lower garment altogether. In Vietnam, it is known as the Ao Dai, distinguishable by the long, hip-length slits up both sides; in the Korean Tang Dynasty, it is the Hanbok. Tibet? The Chupa. In central Asia, inner Uzbekistani women still wear their kuylaks, and men drape their modest tunics over loose trousers and earthy sandals.

Model in Vietnamese Ao Dai

Woman wearing a traditional Tibetan Chupa

Model in traditional Korean Hanbok

In China, the manchurian dress (as it was known) took on the task of a more complex evolution under the influences of mythical lore and lavishly corrupt aristocracies that were insistent on a divisive expression of culture. The elite wore deliciously sumptuous silken tunics embroidered with rich patterns and textiles; whilst the commoners wore plain hempen cloth, which was later replaced by cotton. Amongst the elite, clothes started out being strikingly vivid, but later lost that brilliance, becoming plainer items due to the development that was offset by the Song Dynasty of the twelfth century, from which the dragon robe emerged and became used as a court dress.

Pu Yi, The Last Emperor of China in Qing Dynasty costume ( John Springer Collection/Getty Images )

In Japan, the attire there was strongly swayed by the continental chinese-inspired culture of Korea; an influence which increased with the introduction of Buddhism. The aristocracy of the Nara and Heian periods saw fashion being thoroughly imbibed into Japanese cultural norms and taste was expressed in details such as colour, cut, and ornamental elements without losing the basic theme of the wrapped long robe, even when it later transformed into the now iconic Kimono under the era of the Samurai rule.

A court lady wearing Kimono from the Nara period

Source: thekimonogallery.tumblr.com

Woman wearing Heian-period-style court kimono

Source: thekimonogallery.tumblr.com

The way in which fashion and style found expression, though shamelessly boastful, retained the traditional reticence of the self-expression of Asian conservative values. However, with culture and traditional garb going hand-in-glove, it is unsurprising that certain areas, in retaliation to the Chinese hegemony (which was the most dominant influencer of East Asian cultural wear and fashion), resisted the adoption of their dress. In Manchuria, traditional clothing disappeared altogether at some point; Mongolia’s violent retaliation came in the form of the deel, which was paired with a hat; and in East Turkestan, the revolt against the Chinese took the form of the adoption of Islam and its traditional hijab.

Women wearing traditional Mongolian Deel

Source: upload.wikimedia.org

Women protesting against a ban on wearing the hijab in universities, in Ankara, Turkey

Photograph by BURHAN OZBILICI, AP

Source: nationalgeogrpahic.com

In the 21st century, the fast-fading norm of Asian cultural attire as something purely cultural and not marketed for western consumerism is a resistance that Gurung saw as a necessity when he spied its ancient matriarchy revolving on the barren foothills of his nativity. The colourful Tharu people, who are located in southern Nepal and northern India, express this resistance in their choice to honour their traditional attire, and Gurung joined this resistance by employing the craftsmanship of the Nepali artisans combined with “sebiru” techniques in the production of his couture. The show was blended with western sportswear motifs worn by an impressive selection of models spanning 35 countries.

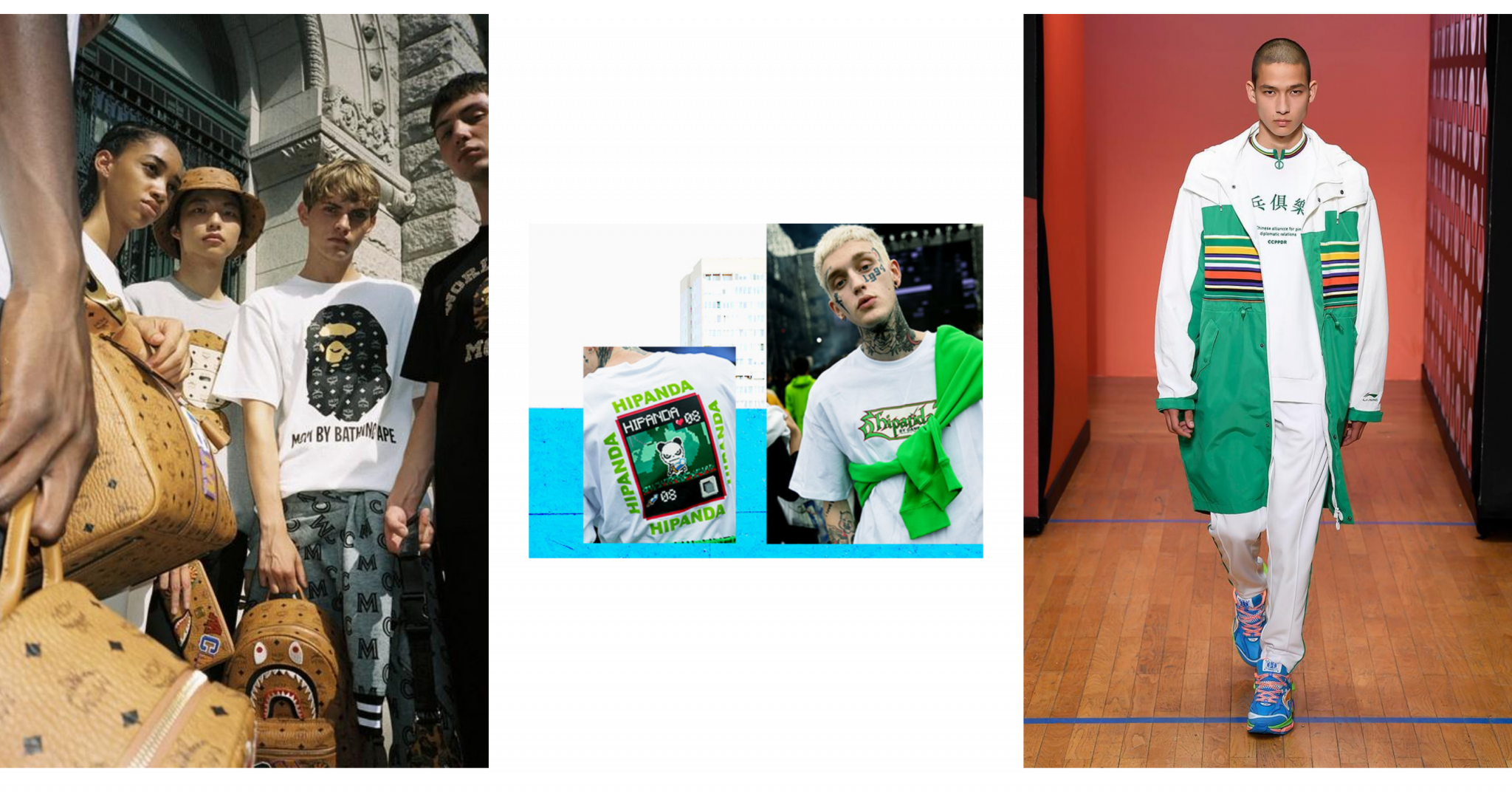

And rightfully so. The bid towards inclusiveness, particularly the inclusiveness of ethnic individuality, is the current, trendy epoch paving the eclectic streets of China and Japan. Fashion is no longer heavily dependant on the sanguinary rules of the royal bhadralok, and cult-status brands like Commes des Garçons, Li Ning, hip-hop’s beloved BAPE (the practical abrrev. of A Bathing Ape), Hi Panda, and the timeless Yohji Yamamoto are all available prêt-à-porter to the ordinary proletariats of you and I.

Popular streetwear brands BAPE, HI PANDA, and LI NING

NPC Fashion Week Paris 2019

Source: chinesegraffiti.com

Model wearing Yohji Yamamoto Spring/Summer 2020 Men’s Wear

Source: Hypebeast

Model wearing Yohji Yamamoto x Adidas Y3 SS19 Collection

Source: Hypebeast

Model wearing Yohji Yamamoto x Adidas Y3 SS19 Collection

Source: Hypebeast

What these brands have in common is the power of either blending or disrupting the social cultural norms of their home-towns through the use of era-spanning interpretations and variety. Elements of taste are now linked to personal identity and the liberties that artistic effusion has to offer; however this does not entail the sacrilegious act of discarding customary significance. Feiyue, a Chinese shoe brand that was specifically designed for Shaolin monks, is seeing a resurgence and “flying forward” into millennial expressionism and fashion staple status. Wookong, a Chinese streetwear brand named after the Monkey King character in the ancient Chinese novel, “Journey to the West”, incarnates symbolic animals that have celebrated and critical meanings in Chinese culture. The quintessential noise-making UNDERCOVER clothes have been at the forefront of the harajuku fashion movement in Tokyo, Japan, refusing to compromise between either element of a punk-Asian demarcation or a high-end fashion appeal. And relatively new kid on the block, KURO (which simply means “black”), translates Japanese culture and craftsmanship into minimalistic apparel.

Feiyue Dafu

Source: haustage.com & Shutterstock

Wookong Apparel

Source: Hypebeast

Model wearing minimalist KURO Spring/Summer 2018 Collection

Model wearing minimalist KURO Spring/Summer 2018 Collection

Model wearing minimalist KURO Spring/Summer 2018 Collection

UNDERCOVER Fashion Week Paris 2019

Source: Hypebeast

UNDERCOVER Fashion Week Paris 2019

Source: youtube.com

The defiantly determined cultural sustenance of Asian tradition through clothes marks the continent’s tradition as a symbol of pride – the kind that the world can also be part of regardless of regional nomenclatures. And while few of us would look to don the breath-taking assemblies of the exhibitionistic parisian classifications de haute couture (it is purely art, after all), we can still dress up for a catwalk on the sidewalk.

Lerato Ramodike is a Pretoria based writer, she’s a novelist, short story writer and visual artist.