The African and Asian Cultura of the Human Experience

A cursory scan of the internet results that cropped up from typing, “What is culture” (sans question mark) in the search bar rewarded me with a lot to think about as a twenty-something and considerably westernized African woman – who gon say I be lady-oh! 😉 Google’s dictionary defines culture as, in the first instance, “the arts and other manifestations of human intellectual achievement regarded collectively”; and in the second instance, as “the ideas, customs, and social behaviour of a particular people or society”. A website identified it as “a way of life of a group of people” in it’s pop-up window.

The etymology of the word “culture” reveals this deeper meaning that is assigned to the word today. The word “culture” is literally the French word “culture”, which was derived from the Latin word “cultura” meaning ‘growing; cultivation’. Therefore, in 19th century late Middle English, the word was used to refer to the cultivation of the soil, and it is from this that arose it’s metaphoric use to mean “cultivation of the mind and human faculties”.

It is this cultivation of the mind and human faculties that represents the kaleidoscopic cultures of the globe. Our focus for this first article in this four-part series will be the Asian and African cultures, whose similarities are as common as their contradictions.

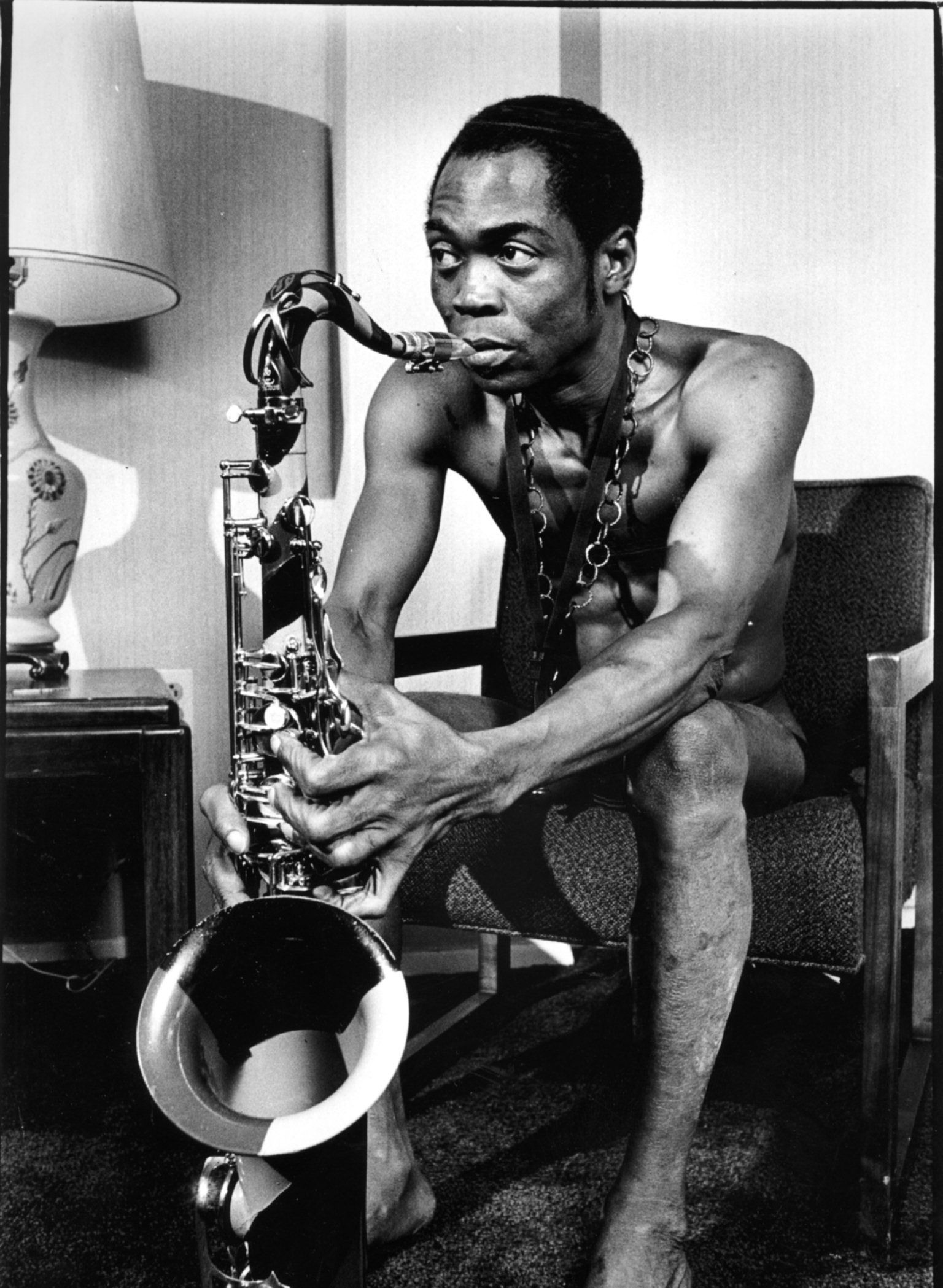

Legendary Nigerian artist Fela Kuti

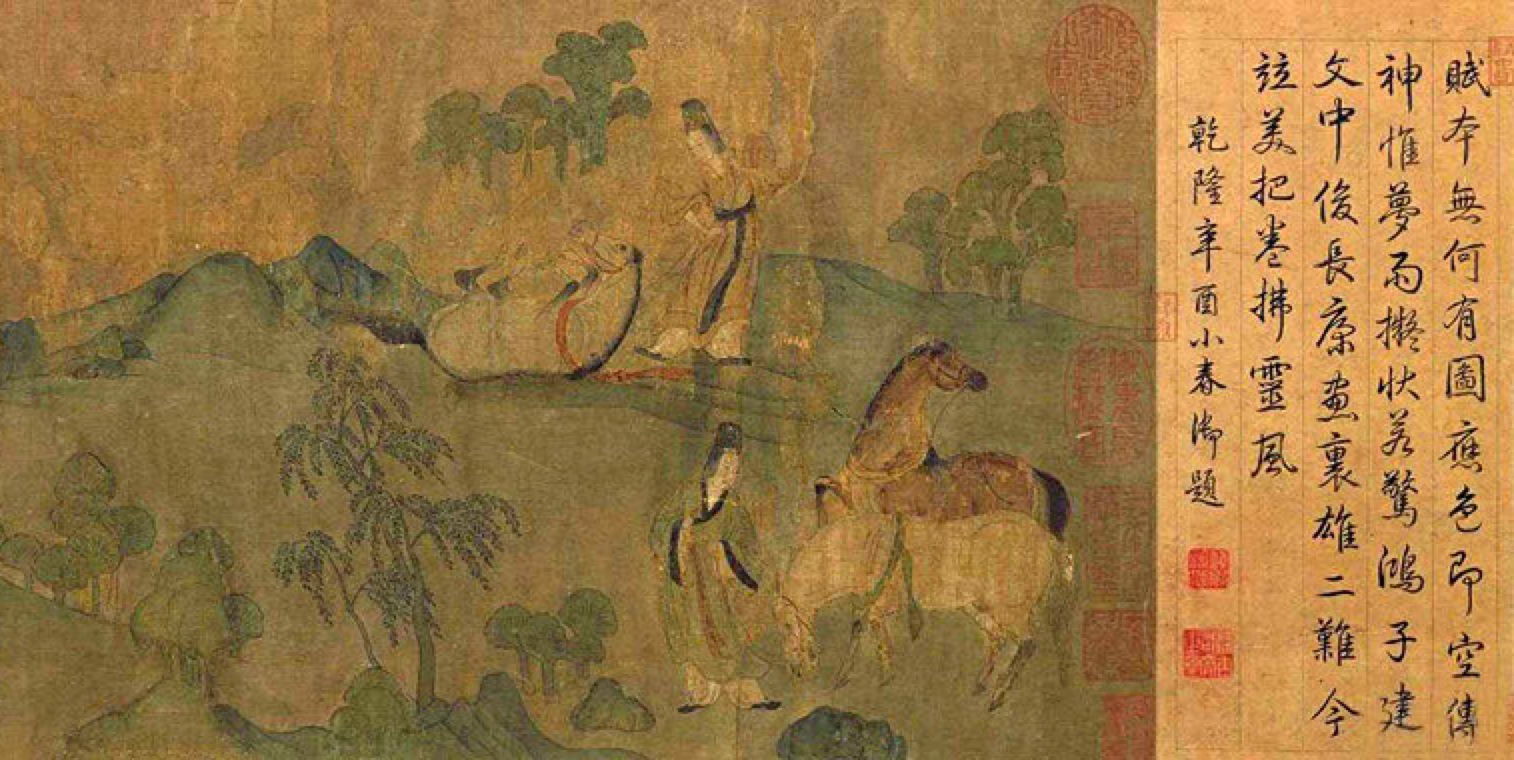

Painting by Gu Kaizhi, Nymph of the Luo River

Painting by artist Amrita Sher-Gil, Bride’s Toilet, 1937

Source: Wikipedia

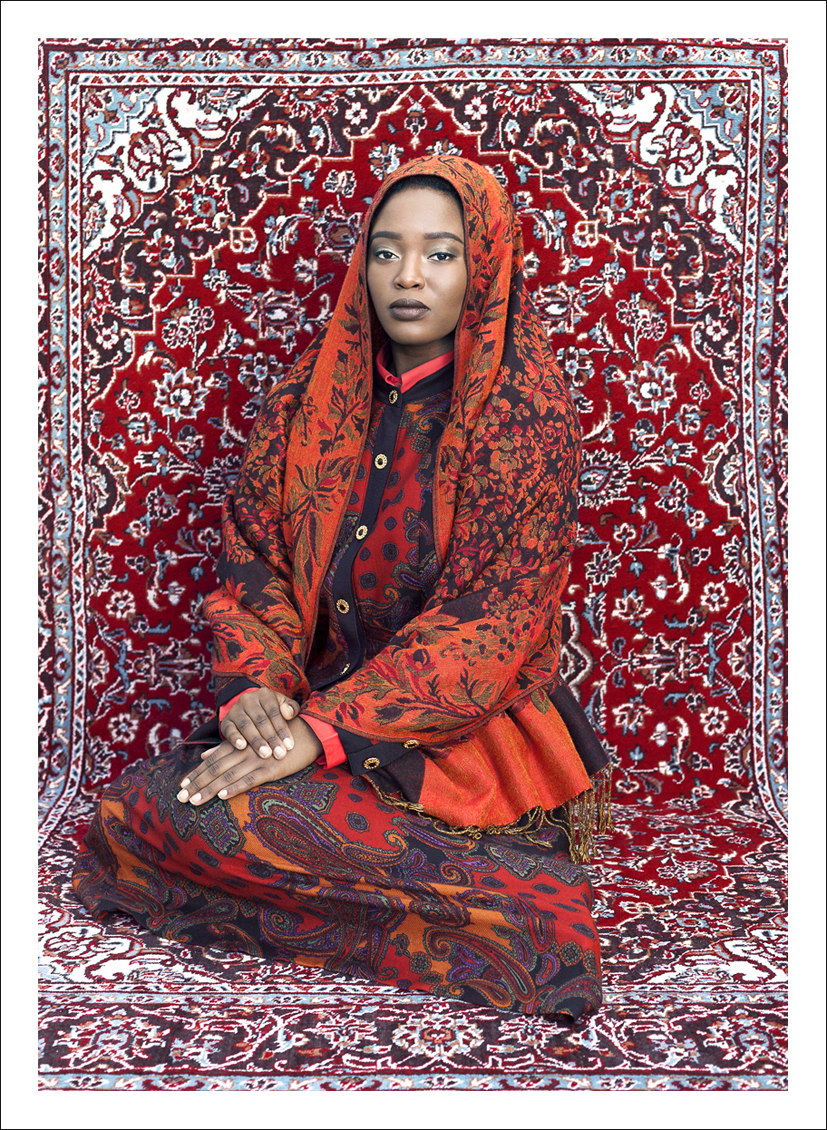

Self portrait by Tony Gum, Indian Lady, 2014-2015

Source: Christopher Moller Gallery

Despite their shared colonial histories, Africa and Asia are a culturally proud people. Their lands are brimming with incalculable beauty, from the memnonian colossi that are the Himalayas to the arid deserts of Africa; both of which manage to cultivate their own inhabitants. And the people are just as rich and diverse as their landscapes: Asia has an estimated number of 635 tribes, while Africa is composed of a staggering 3000 tribes (which is the most amount of tribes in all the continents)! In both instances, diversity is something that most of the countries in these regions welcome, with governments giving legal recognition to the various languages and making efforts to officiate some of the cultural practices of the ethnic people in their countries.

Because of the vastness of the continents in land and culture, it was extremely difficult to settle on only a few cultural identifiers and not talk about all of them – from the elephants and how they are revered in their societies, to their gods and the shared similarities of the cosmogonies and ancient philosophies. However, we ended up settling on five cultural identifiers – and the last one is arguably the most favourite of all, because it truly represents the heart of what Asians and Africans stand for.

The Colossi of Memnon stone statues in Egypt

Source: Wikipedia

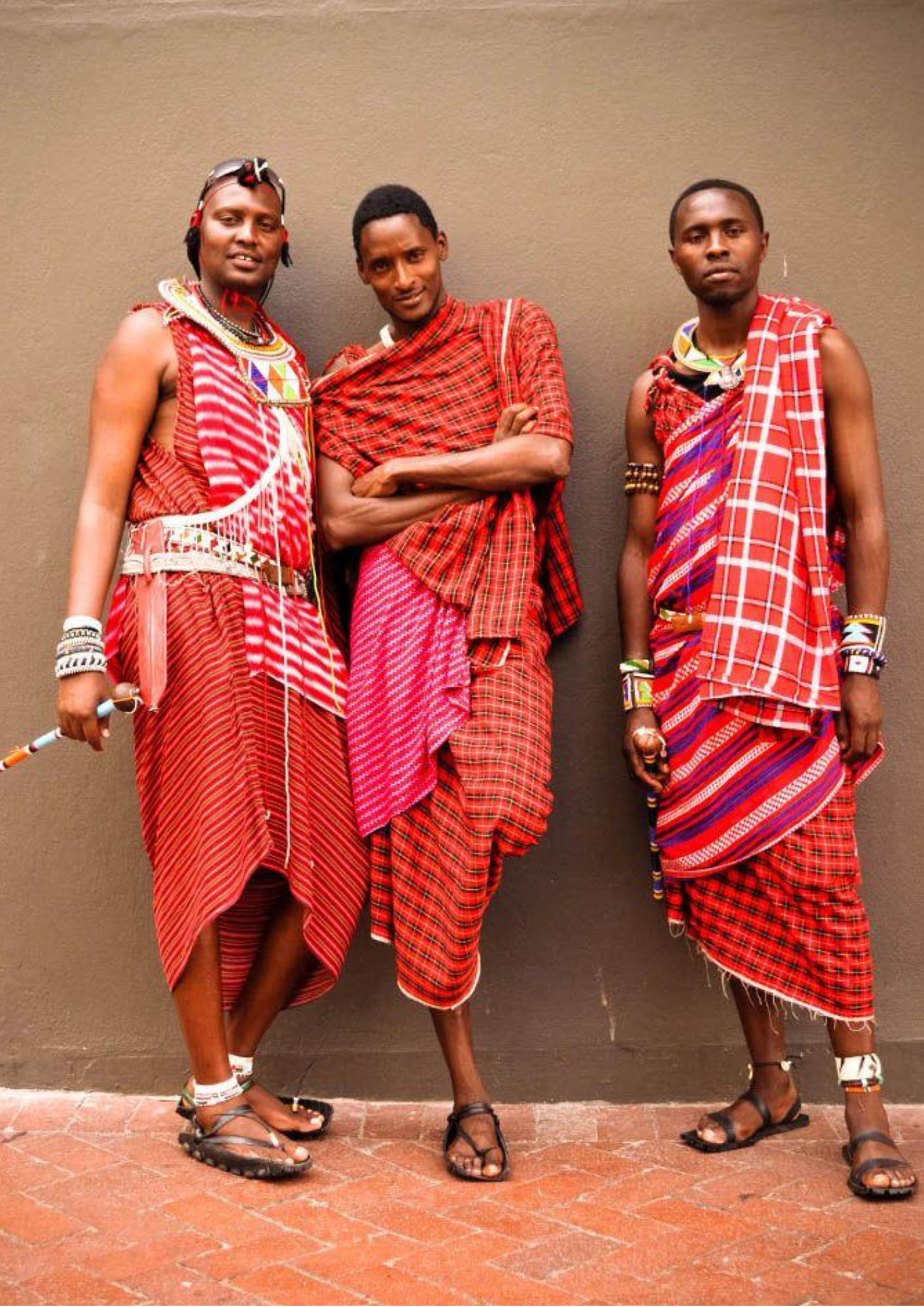

The Art of Clothing

If you love colour, you’ll love the cultural wear of both African and Asian countries. Generally speaking, Asian and African cultural wear emphasises elements of comfort, beauty and symbolic identification. It often resembles exquisite drapery; think the beautiful and brightly patterned flowing dresses seen in Nigeria and Senegal, a style that you’ll find in most of Africa, as well as in Asian countries, like Vietnam and Japan. Men are traditionally seen donning shirt-dresses, a loose garment that can either have buttons or none. This modest cultural dresscode is almost always complimented with elaborately designed headgear in the form of fabric and beads. Design and dress code are a fashion statement that is often used as a medium through which individuals distinguish themselves, like in instances where beads and gemstones are indicators of material status and rank in societies. Another example would be the married women of India and the Turkana women of northwest Kenya, who wear a necklace that bears the same function as a wedding ring and is seen as a symbol of love and goodwill.

Kenyan men dressed in traditional Masai outfits

Source: Pinterest

Turkana bride of Northern Kenya wearing beaded collar necklace

Source: Google Arts & Culture

Creator: Angela Fisher & Carol Beckwith

Cuisine…and Fresh Fruit

Both Asian and African countries boast some of the longest lifespans in the world, and with good reason. The abundant rich, fertile soils of these lands (with the soil being a deeply rich black in some places) produce some of the most lush crops and vegetation you will ever see. It is therefore quite common to walk through villages with yards full of trees that hang engorged with the current season’s fruit; and in the backyard, the grounds burst green with vegetable patches. In Africa, Uganda is considered to be the ‘Fruit Basket of Africa’, with over 50 different varieties of banana – yes, plantain included, whereas China is the world’s leading supplier of apples, with over 2 million apples harvested in the season of 2016.

In addition to local fruits and vegetables, the cuisine of both regions traditionally consists of locally grown cereal grains, as well as milk and meat products from livestock, with India being the world’s biggest producer of milk. The diets predominantly consist of lots of rice, cassava, sweet potato, yams, and fish in the coastal areas, which both continents have. Furthermore, Asia and Africa are either notorious or beloved for their generous use of spices in their foods, with some well-known dishes being the curries of India and Thailand, the jollof of Ghana and Nigeria, and the vegetable stir-fries that are popular throughout.

Plantain also known as Gonja from Uganda

Some Cassava roots

Yams from Nigeria

Nigerian Jollof rice

Traditional Medicine

Traditional medicine and herbal remedies are an ancient and common practise in most Asian and African societies. In 2007, the South African government recognised traditional healers as “traditional health practitioners” under the Traditional Health Practitioners Act. Because of their shared colonial histories, there is an over-arching theme in Asian and African governments to make efforts to encapsulate the cultures and traditions of their nations by giving their practises and beliefs as much legal consequence as is possible.

In terms of the traditional medical practise itself, there is a heavy reliance on natural remedies. In both Asian and African regions, ailments are often viewed as phenomena that extend beyond the mere physical. Traditional healers are thus called to heal both the body and the mind, with an emphasis placed on the spiritual elements of the injury or sickness. In Africa, healers are guided by their ancestors in identifying the root cause of an illness or disruption of the soul. It is also a common practise to view bad luck or misfortune that befalls an individual, a family, or a community as something that a healer can offer a solution for. In India, Aryuveda is the dominant traditional medical practice, which is a healing system that also focuses on the fundamentals of balancing the body, soul and spirit in order to afford longevity and wellness. In China, herbs, acupuncture and homeopathy are some of the primary tools in treating illness and ensuring good health. Exercise is also central to both Chinese and Indian medical practise, with India being well known for yoga, and China for the practise of tai chi – which was developed from yoga. Overall, the experience of traditional medicine in both African and Asian countries is something that is intrinsic to the daily lives of the people, with a philosophy that healthy eating habits and lifestyle choices are the primary sources of ensuring one’s good health.

Dhanvantari, an avatar of Vishnu, is the Hindu god associated with Ayurveda.

A Spiritual Way of Life

This emphasis on the spiritual and supernatural that we see in the traditional medicine typifies a prevalent belief in the existence of alternate realms of reality. A belief in a pervasive “spirit” is an intrinsic part of the way of life of the people in Asian and African tribes, and it is a belief that informs their conduct and mythos. Cultural religious doctrines and beliefs inform a large part of the function of societies, with the practise of rituals and the observance of certain feasts and celebrations taking place on a yearly, monthly or weekly basis. For example, in Zimbabwe there is a ritual referred to as “Bira”, which is a ceremony wherein the members of an extended family invoke the ancestors for guidance and intercession. In the Asian countries of Taiwan, Hong-Kong, China and Macau, a similar festival in which ancestral spirits are invoked is known as the Qingming Festival. Both rituals take place during the time that is after the winter and before the rainy season.

Such communication with their ancestors and gods is a way of life that most people are constantly aware of. The ethnic tribes in these areas see themselves and everything that exists as being dualistic in nature, and they consider themselves to be both a spiritual and physical body. To them, ancestors or the gods are merely human beings and loved ones whose ‘essences’ or ‘souls’ have left the material earth through the death of the physical body, and are now dwelling in the spiritual realm whose effects can be felt and seen on the physical.

The Humanity of the People: a Core Value

The conduct of the people of any ethnic group reveals a lot about the nature of what they live by and it exposes the core values of their cultures. Asian and African people are typically friendly, open and they get along well with one another. They are often kind and respectful, with many of the people being open to different cultures, despite their humble conservatism. Their families are often large, with members being encouraged to form bonds and friendships beyond their immediate nuclear families, and it’s a practise that translates to the communal way of living that has been observed in most Asian and African countries.

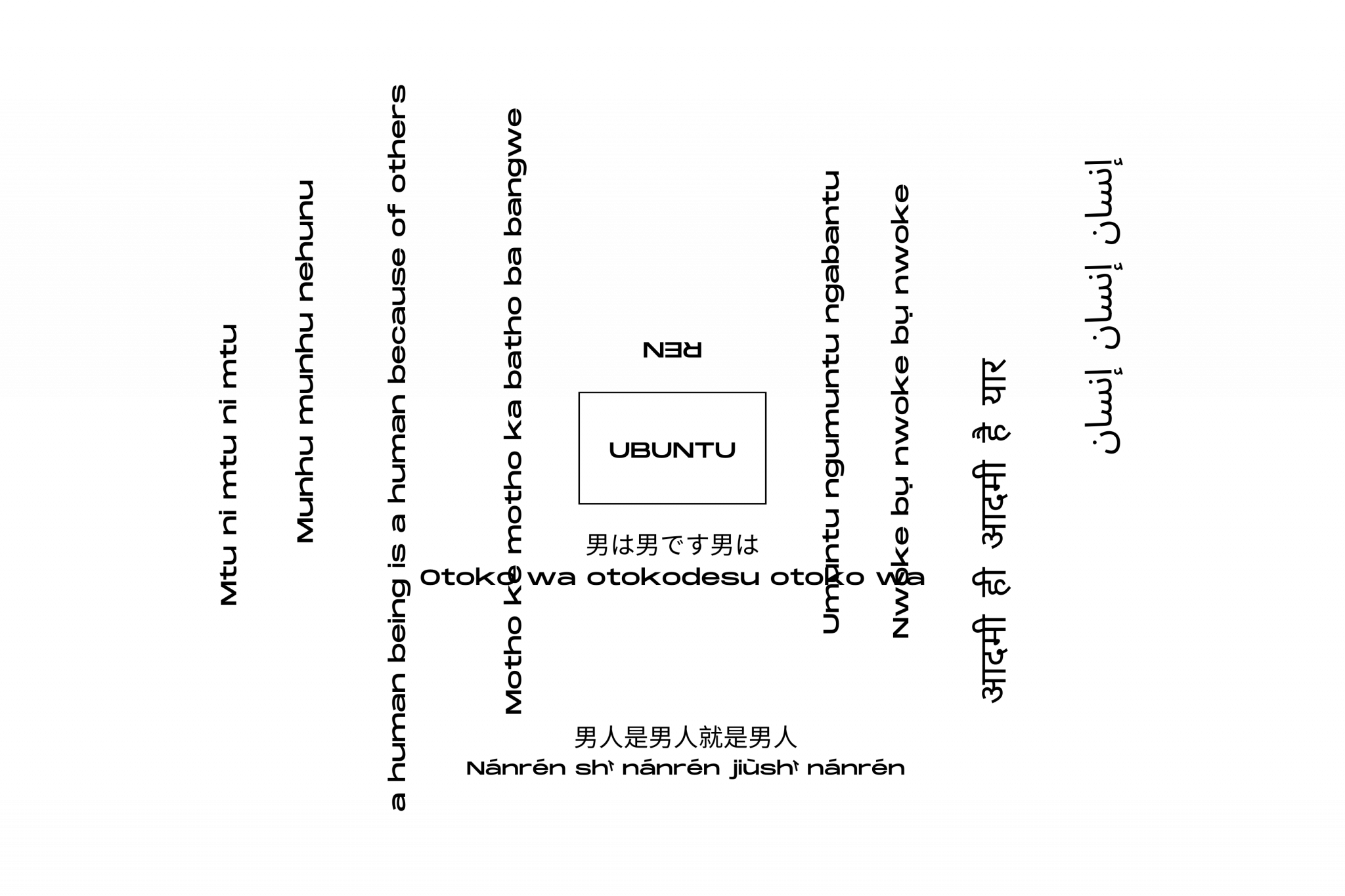

The term “communal” is an adjective which describes something that is used or shared by everyone in a group. It is this sense of sharing that is considered to be one of the most pivotal experiences in African and Asian communities. In the Confucian period, this sense of community was described in the statement, “Ren juishu youren.” In several African languages it translates to, “Motho ke motho ka batho ba bangwe” in SePedi; “Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu” in isiXhosa; and “Munhu munhu nehunu” in Shona. In English, this powerful phrase means, “I am because we are” or “a human being is a human because of others”. It is this philosophy of a belief in a universal bond that connects all of humanity that is at the heart of African and Asian ethnic groups. It guides their perceptions of how they relate to one another as sharing in the human experience, and it is seen as a principle that connects all life. This “humanity”, which is “Ren” in Chinese and “Ubuntu” in siZulu, gives the African and the Asian individual a moral compass to measure the way in which they conduct themselves towards one another and towards all life forms. It informs the recognition of the divine spark or godhood in everything that exists. Therefore, compassion, empathy, love, perfect virtue, benevolence, goodness and human- heartedness are seen as expressions of this divinity, or this ‘humanity’. And it is upon this ideal of humanness that Asian and African cultures cultivate their minds and human faculties through the vehicles of artistry, music, community and individual growth.

Ubuntu, African saying

“Our culture provides us with an ethos we must honour in both thought and practise. By ethos, we mean a people’s self-understanding as well as it’s self-presentation in the world through its thought and practice in the other six areas of culture. It is above all a cultural challenge. For culture is here defined as the totality of thought and practice by which a people creates itself, celebrates, sustains and develops itself and introduces itself to history and humanity.”

– Mualana Karenga, African Culture and the Ongoing Quest for Excellence

Lerato Ramodike is a Pretoria based writer, she’s a novelist, short story writer and visual artist.